By Amy Arnett

By Amy Arnett

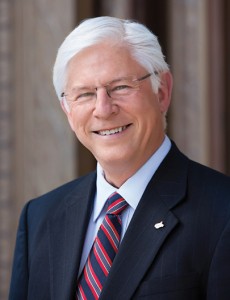

Keith Burdette has been a public servant for West Virginia since the age of 23. He began by serving two terms in the West Virginia House of Delegates before being elected as the youngest State Senate president in the state’s history at 34.

In 2010, Governor Earl Ray Tomblin named Burdette cabinet secretary of the West Virginia Department of Commerce. Burdette also serves as the executive director of the West Virginia Development Office and oversees the divisions of Energy, Forestry, Labor, Natural Resources and Tourism; the offices of Economic Opportunity and Miners’ Health, Safety, and Training; WorkForce West Virginia and the West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey.

West Virginia Executive had the pleasure of meeting wit

h Burdette to discuss several aspects of the state’s economic outlook, and the conversation inevitably turned to West Virginia’s role in powering not only the nation but the world.

As a proud West Virginian, Burdette has long been aware of the power of energy here. His role with the state enables him to be an expert on many Mountain State topics, and as one of the state’s most powerful advocates, he believes West Virginia is something to brag about.

With an evolving presence in multiple industries, including a position as a hub for the rebirth of manufacturing, West Virginia has everything to gain in the coming years. One of the state’s emerging assets in industry is the ideal position for distribution for the Northeast market. The Eastern Panhandle, for instance, has proximity to major metropolitan areas along the Eastern Seaboard, making it an ideal site for manufacturing development and expansion.

One of the most important steps in the process of creating an industry boom, says Burdette, is getting West Virginians to be involved in their futures, especially through work force training and community development. The Development Office has spearheaded projects this year ranging from the preliminary selection of an ethane cracker site—a potential economic game changer for the state—to the establishment of work force training programs to the expansion of a Wayne County plant that supplies components to nearly all the world’s top automakers.

Though challenges lie ahead for West Virginia, the future is also undeniably promising.

WVE: As the executive director of the West Virginia Development Office, what do you see as your role in promoting the state and creating new opportunities, especially in the energy industry?

KB: I always tell people I’m the number two salesman in the state—number one is the governor. My job is to be a liaison and facilitator, and I’m very comfortable in that role.

I’m incredibly passionate about our energy industry. We are at a unique moment in the state’s history, and the decisions we’re making right now will be critical for the next 50-75 years. These decisions will impact generations, and people will hopefully have jobs in this state because of what we are doing: developing infrastructure that will guide industry and create a re-emergence of manufacturing along the way.

WVE: What can you tell us about the current economic trends of the energy and manufacturing industries in West Virginia?

KB: As you look across the whole sector, the trends are a little mixed.

Coal has had a challenging couple of years. Some of that is certainly caused by increased regulation in Washington, D.C., but there are a lot of purely economic pressures on coal. The long-term trends for coal are not completely negative. We are the second largest exporter of coal in the country and the prime source for metallurgical coal, which is the key component for making steel. Coal will continue to play a prominent role in the West Virginia economy. It employs more than 20,000 people—and those are direct jobs; the indirect jobs it produces are as many as three to four times that.

Coal’s key role will also impact the nation’s energy economy, like it or not. There are many places in the world that tried desperately to get away from coal, and those efforts have largely failed. It’s cheap, and it’s abundant, so we see a role for coal here.

Natural gas has now become an abundant, cheap energy source. The natural gas economy is evolving as we speak; every day, it’s changing. Five years ago, there was no expectation in this country for a rebirth of manufacturing because the natural resources weren’t here. Now, there is optimism in the country—and our state—with the advent of shale gas, specifically the unique combination of gas and liquids available in the Marcellus region. It has changed everyone’s calculations on both the value of natural gas and the opportunities associated with liquids and manufacturing.

WVE: Can you expand on the relationship between the natural gas industry and manufacturing and why that is a key component in the outlook of a manufacturing renaissance?

KB: What we have here in a narrow portion of the Marcellus and Utica shale plays is what they call the wet gas zone. It runs largely along the Ohio River from Tyler County through the Northern Panhandle into Pennsylvania and New York. Inside that, there is abundant natural gas, but more significantly, it is thought to have some of the world’s largest deposits of ethane.

I would say more than 90 percent of manufactured goods have an ethane-based component, and that’s why you’re seeing massive infrastructure development across the state and in the region. Inside natural gas liquids, there is ethane, butane, propane, pentane and natural gasoline. Those components are extracted all at once then separated, but the ethane has to be separated through a different set of infrastructure called de-ethanization.

The ethane is then transported to crackers where the molecules are cracked to form ethylene, and ethylene is the motherload for manufacturing. It’s the key feedstock for manufacturing fabrics, carpets, plastics and several other things.

WVE: Tell us about the history of the natural gas industry in West Virginia and how you are working to create an environment where a manufacturing boom can take place.

KB: West Virginia has been a producer of natural gas for maybe 200 years. The first ethane cracker in the world was patented and developed right here in the Kanawha Valley in the 1920s by what was the pre-cursor to Union Carbide. The first petrochemical industrial complex was here, too, and it’s all because the feedstock was here.

Once upon a time, ethane was prevalent here, and it just went away. When it went, about 18,000 jobs went with it. It will probably not be the same, but the opportunity to do something similar is very real to us again.

What West Virginia is doing is not only developing the gas fields but trying to create an opportunity where we get to—for the first time in a long time—take those natural resources and create value-added products.

For natural gas, the risk is not doing anything, not moving forward at all. We’re not going to do that. There are certain areas that are paralyzed by that risk, but we have consistently led on several fronts. Fracing is a risk—or at least, people perceive it as one—but we have 50 years of fracing experience in this state. We were one of the first states to draw up, legislate and approve rules for that operation.

There will come a day when they quit drilling, but that doesn’t mean they quit extracting. They will put a valve on there and keep pumping long after the drilling operations are gone, and that’s what we want to be a part of. We have worked hard to attract billions of dollars in infrastructure development to West Virginia through separators, de-ethanization structures and, now, pipeline structures and cracker projects. The next step in the equation is downstream development: companies taking the products from a cracker and turning them into consumer goods.

WVE: With the rapid changes taking place, what role will exporting play in West Virginia as the state evolves with the energy industry?

KB: We have become the exporter of energy for most of the country. The rest of the country doesn’t realize how reliant they are. If West Virginia pulled the plug, there would be chaos without access to coal. It should be an all-of-the-above energy economy, and there needs to be a fair system recognizing that.

Federal government rules on coal are quickly exceeding the technology to meet them, and that’s when it becomes an unfair playing field. Our state has always supported efforts to develop clean coal technologies; in fact, Senator Rockefeller just introduced legislation to force more money into it. But when rules are passed that exceed technologies, the mission is clear, and it’s just unrealistic.

For natural gas, we suddenly have one of the biggest gas field not only in the country but in the world, probably only exceeded by the Persian Gulf. We are target number one on a lot of lists. There are other shale gas plays around the country, but none of them have this expansive area of liquids.

In West Virginia, we see energy as a whole as not only our past but our future long after we’re gone. Our goal is to take those resources and create opportunities that go beyond energy creation.

WVE: With so much interest in our natural resources, how can West Virginia use its central role to its advantage?

KB: I’m a West Virginian, and I’ve watched us be an energy extraction location all of my life. This is an opportunity. If we can keep just some of our resources here, we can do great things in the long term. There is a place for all of it, but there’s also a place for us.

It’s awfully tempting for those in the industry to just stick everything in a pipeline. There is huge pressure and billions of dollars at stake in the Gulf Coast where there is already a massive infrastructure in place, and they’re just looking for ways to feed it. One ethane cracker will consume between 60,000 and 80,000 barrels of ethane a day, so they want to stick a straw in us and suck it to the Gulf Coast.

One way or another, we have to make it clear that they cannot take all of our resources out of this region to someplace else. We’re just not going to stand for that. We’re not going to simply be an energy colony for the rest of the country; we need to be a part of the economy that is going to grow because of it.

We don’t expect everything to stay in the state; there’s no expectation of that, and we don’t think it’s responsible. As I started by saying, the decisions we’re making will have an impact for decades to come. We know that if it’s gone, it’s gone. We’re just a little state trying to compete, but we’re doing fairly well.

WVE: How important is diversification to both the state’s future and its economy?

KB: Our struggle is also our strength in that the history of the state is wrapped up in the energy industry. It’s more than just coal and gas. We’re into wind turbines and hydro and solar power. The largest wind turbine field east of the Mississippi is in West Virginia. We’re doing all of those things, but coal and gas are dominant players.

In the last three to four decades, West Virginia woke up one day and realized we couldn’t just be about one thing. If you look across the state, you’ll see a pretty broad diversification of the economy. We’re into automotive, aerospace, high-tech, distribution and fulfillment, and we want to continue those efforts. We put our resources with companies, many times smaller ones, who have the opportunity to get comfortable in West Virginia and grow here.

WVE: As head of commerce and development for the Mountain State, what do you see as the benefits of doing business here?

KB: West Virginians are sometimes a little self-conscious, almost apologetic. When I go out and tell others about the state, so many of them say, “I had no idea.” When we talk, for the first time in a generation, we get to say we beat a lot of other states on a variety of issues. Our workers’ compensation rates are lower; our corporate tax rates are lower; our unemployment trust funds are stronger. Issue after issue that is important to businesses, we’ve tackled them. Now, guys like me can go say, “Other than flat land, we have everything else.” We can do it cheaper and do it better, and we’ve not always been able to say that.

We didn’t just start yesterday, and that’s the big difference. We started 20 years ago. I guarantee you I won’t be in state government when we’re finished working on some things, but I can tell you we’re halfway through some of it. It’s making a huge difference. One day, when today’s children are running the State of West Virginia, they’re going to have resources that none of us have now because our problems were approached reasonably and intelligently.