By Rebekah Karelis

The name Mail Pouch usually evokes a visual image of an idyllic barn in a pastoral setting and an automatic sense of familiarity with the product. Perhaps the country’s most well-known outdoor advertising tool, the surviving landmark Mail Pouch barns are important and treasured pieces of Americana. What many people don’t know is that Mail Pouch Chewing Tobacco was a product of West Virginia.

In 1879, Aaron and Samuel Bloch began operating a stogie-making business on the floors above their wholesale grocery and dry goods store located on Main Street in downtown Wheeling, WV. A disastrous flood hit the town in 1884, and the floodwaters destroyed the business located on the first floor, wiping out their stock and equipment. The tobacco factory, though, remained untouched on the second floor.

The brothers sold off the damaged goods and turned the focus of their business efforts wholly on tobacco production. They created Mail Pouch Chewing Tobacco in 1879, which was comprised of tobacco wrapper clippings that resulted from the stogie-making process. The brothers gathered, flavored and packaged these clippings for sale. With the success of this tobacco product, they eventually discontinued stogie making and exclusively sold this cheap chewing tobacco option.

The Bloch brothers began buying tobacco leaves for their product from crops in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Connecticut and Ohio to be blended at the facility in Wheeling. The crops would then be formed into blocks and cut with a ribbon-cut technique. The brothers took the idea one step further by deciding to flavor those wrapper clippings and package them in a bag inspired by those used to transport mail on the railroads, hence the birth of Mail Pouch Chewing Tobacco.

The practice of selling stogie wrapper clippings was not a new idea at the time, as many businesses were doing the very same thing. Even though the Blochs were not inventing the wheel with their product, it was their remarkable advertising campaign that left an indelible mark across America’s countryside.

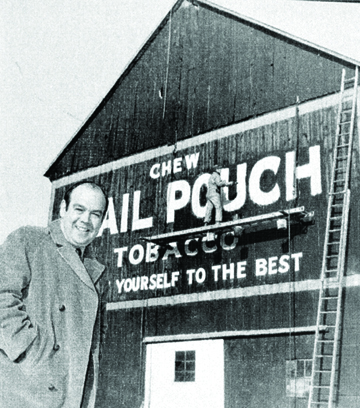

Their well-known advertisements began to appear on barns across the country around the turn of the century. During the 1920s, in Syracuse, NY, six men—two per truck—began painting barns, traveling from site to site by way of Ford Model T’s. Focusing their efforts first on barns along railways, the common slogan, “Chew Mail Pouch – Treat Yourself to the Best!” later popped up along rural roads in distant countrysides and town centers from Maine to California.

As an advertising campaign, it was brilliant. The farmers were offered their choice of payment for use of their barn, most of which needed painted anyway: money, tobacco or a magazine subscription. Eventually, the payment simply became cold, hard cash.

Designed by Mr. J.A. Bloch, the sign required a wide, yellow border with a black spot centered in every foot. At one point, for a painter to be paid, he had to submit a picture of the advertisement. The painters were paid per square foot, and in that picture, the central office could determine how many square feet the advertisement covered by counting black spots.

The paint of choice was Dutch Boy white lead, a paste mixed with linseed oil and stored in milk cans between jobs. Painters would then thin it with gasoline before applying it to the barns. To achieve the characteristic black on the barn side, they would use lampblack mixed with linseed oil. The words “Chew” and “Treat Yourself to the Best” were typically in white, and “Mail Pouch Tobacco” was in yellow. While every team stuck to a prototype, there were variations from region to region.

In the beginning, local painters were hired to paint the barns in their area because transportation from region to region was so difficult. In later years, as transportation routes and means improved, the paint contracts were pared down to teams of painters that would travel regionally. They were assigned a territory and would stay in one area for several weeks, painting as many barns as they could.

In 1933, brothers William and Ed Burner took over the business—William took over the western half of the country and Ed took the eastern half. It was during this period that the company moved away from hiring local painters and began hiring official barn-painting crews who traveled the country. Each territory could be covered in about three years’ time, with the teams painting barns from February until the end of December, depending on the weather.

Harley Warrick, the last of the barn painters, spent 38 years painting Mail Pouch logos on barns across the country. Born in Belmont, Ohio, he began working as a barn painter after he returned from World War II at the age of 21. He worked for a sign shop first, and when a team came to his family’s farm to paint their barn, they had an opening on one of their four two-man teams. The painters were paid $28 a week plus incentives per square foot of barns painted, and added incentives included staying in hotels at the company’s expense and traveling in a company truck. His team would paint two or three barns a day, six days a week which would equal out to approximately 700 barns a year.

In 1965, Congress passed the Highway Beautification Act, supported by Lady Bird Johnson, restricting many new barns from being painted as it called for no sign to be within 660 feet from both interstates and primary highways. This law was enacted in order to banish “eye pollution,” and it changed the barn painter’s life forever. The barns Warrick painted were considered a billboard after this law was passed, and it greatly limited those that could be painted or repainted.

In fact, the company had to fight in order to save those that were already in existence by 1965. With the help of West Virginia Senator Jennings Randolph, Congress amended the law in 1974 to exclude signs “on farm structures or natural surfaces,” or, as in this case, of historic or artistic significance. The Senate Committee ceded that there were some types of outdoor advertising that were unique enough to justify their preservation, and at the top of their list was the Mail Pouch barns.