Supply Chain, Workforce & Innovation

By Samantha Cart

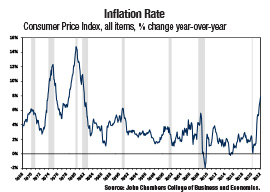

As countries around the world work to repair economies upended by the COVID-19 pandemic, the war between Russia and Ukraine is creating even more difficulties while exacerbating existing issues, including worker shortages; commodity, transportation and inventory disruptions; and the highest inflation rate in a generation in the U.S.

However, these crises have also shed light on existing weaknesses and presented an opportunity for building better, stronger workforces and supply chain networks by implementing digital technology, building capabilities and encouraging market diversity and supply chain transparency. While this will require innovative thinking and entrepreneurialism, the potential impact is significant.

To offer understanding and a state, national and global perspective, West Virginia University (WVU) John Chambers College of Business and Economics’ John Deskins, John Saldanha and Ednilson Bernardes shed light on these important issues and their economic impact.

Supply Chain Disruption on a Global Scale

In April 1993, I witnessed a different supply chain disruption involving Ukraine and Russia firsthand. On April 11 of that year, the freighter, on which I served as a trainee second officer, docked in Nikolayev—today known as Mykolaiv—one of the largest ports in the then brand-new country of Ukraine to load urea from post-Soviet Russia. Besides the winter weather related delays and a financial crisis that saw four-digit inflation in both Russia and Ukraine, we loaded just half the load in 17 days. The freighter waited at anchor in the Dniprovska Gulf at the mouths of the Southern Bug and Dnieper rivers for nearly three months. After that, we loaded some of the balance in Odessa before sailing out with less than our full promised cargo of urea.

Fast forward nearly three decades, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine has precipitated disruptions across a broad swath of supply chains, from fertilizers and food commodities to automotive and high-tech. From a supply chain perspective, the effects of these disruptions can be classified into commodity, transportation and inventory.

Starting with commodities, Ukraine is widely regarded as the breadbasket of Europe. When the invasion began, The Wall Street Journal reported that Russia and Ukraine’s combined products account for nearly a third of the world’s wheat exports. In addition, nearly one-fifth of corn and 80% of sunflower oil exports originate in Ukraine. While reading this, I absentmindedly checked the nutrition facts of my breakfast cereal to find sunflower as a listed ingredient. In the short run, it is unlikely the Ukrainian invasion will directly affect these seasonal food commodity prices, some of which we don’t import into the U.S. However, as the war drags on and these crops are not planted, we can see a severe shortage of these essential commodities, which will push food prices up, affecting inflation and consumers’ wallets.

While some of these commodities can be substituted, it will take time and cost to do so, which manufacturers will pass on to consumers. Furthermore, it will put pricing pressure on related commodity markets. This is exactly what is happening with fertilizers amid Russia’s efforts to slow and even stop fertilizer exports. According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Mineral Commodity Summaries, Russia is the second largest exporter of potash fertilizer in the world. While the U.S. imports most of its fertilizer from elsewhere, countries dependent on Russian fertilizer, like China, will look to alternative suppliers, pushing up prices for U.S. farmers and ultimately consumers.

Aside from disruptions to food commodities, oil and natural gas, which pushed prices upward soon after the invasion, the war has disrupted a number of more esoteric commodity and component supply chains that can have wide-reaching impacts. For example, the semiconductor supply chain, barely recovering from the pandemic disruptions, faces a new disruption from neon used in lasers at the lithography stage of chip manufacturing. The USGS reports that a substantial portion of the world’s supply of palladium used in automobile catalytic converters comes from Russia. Relatedly, international sanctions can affect substantial supplies of rare earth metals like vanadium, originating in Russia and used to manufacture electric vehicle batteries. Even a lack of components, such as electric harnesses originating in factories in Ukraine, can shut down production at assembly plants for Volkswagen, the second largest auto manufacturer in the world. The results of all these disruptions can be distilled down to one simple but hard truth: higher prices for the consumer.

We are all familiar with the pandemic shutting down seaports such as Long Beach in California, holding up everything from electronics and home appliances to building supplies. One of the safety valves was air freight, with several passenger airlines converting airplanes for freight to make up for the lack of passenger traffic. The other was the Trans-Siberian Railway shipping containers from Pacific Rim countries, like China, to Western Europe. The Trans-Siberian Railway is no longer an option, and the cost of air travel will increase as flight paths have to be altered. Fuel costs are going to push up the cost of transportation in general, while the destruction of Ukrainian Black Sea ports is going to exacerbate commodity shortages long after the end of the war.

Inventory in supply chain management is typically used to balance the mismatch between demand and supply. Firms don’t want to run out of product, which will affect their revenues and customer confidence in the short term and eventually market share in the long term. In the short term, firms order more to stock up on inventories, which will push prices up. This has two effects pushing inventory holding costs higher. First, firms must now finance higher priced inventories for longer. Second, as transportation capacity comes under pressure, increasing the length of time to move items across the globe, firms will have to finance longer pipelines of inventories while they are in transit. While this will add to the prices consumers pay at checkout, this will also require firms to have greater cash reserves to service these costs.

In summary, the Ukrainian invasion has affected all three levels of supply chain management. Since the pandemic, several firms have already evaluated their global supply chain vulnerabilities, looking at nearshoring and re-shoring to reduce their vulnerability to the vagaries of global instability. I contend that the leadership of every firm must do the same to reduce their exposure to global instability.

West Virginia’s Battle With Worker Shortages

As we continue to recover from the severe recession brought on by COVID-19, some unexpected economic challenges have emerged that are placing new stress on our nation’s economy. I write to consider one such challenge: widespread worker shortages.

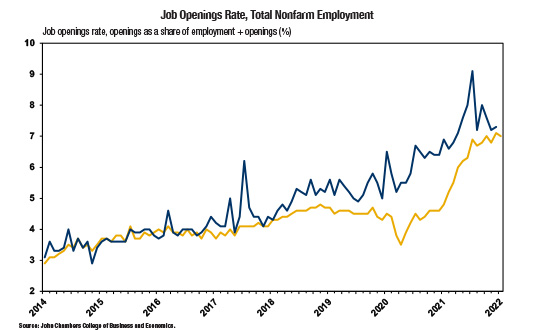

Over the last year, it has become readily apparent that widespread job vacancies have appeared, creating a variety of issues ranging from minor inconveniences in some places to severe challenges in others. To illustrate, the job openings rate in West Virginia, which represents job openings as a share of total filled jobs plus job openings, now stands at just over 7%. This means that employers are currently unable to find the workers to fill over 7% of all the positions they need to fully operate. This represents a substantial increase in this figure, which typically ranged between 3-5% in West Virginia in the decade leading up to the COVID-19 recession. Although this is a national problem, the job openings rate in West Virginia is slightly above the national figure.

Fortunately, not every sector of the economy has been significantly affected by this worker shortage. National data show that the shortages are most pronounced in the super sectors of trade, transportation and utilities; leisure and hospitality; health care; and other services. The trade, transportation and utilities sector includes retail jobs, and the leisure and hospitality sector includes restaurant jobs—two areas where worker shortages are visible to everyone. The sector economists term “other services” includes several service industries that involve close, in-person contact. Job openings in the health care sector are understandable given the immense stress workers in that area have faced over the past two years.

Many of these job openings are some of the lowest paid positions in our economy. This is understandable, given that workers farther down the corporate ladder are often tapped to fill a higher position in the same company or industry, leaving the lower-paid positions vacant. This also matches with the noticeable jump in the quits rate that we have observed in recent months. This statistic captures the number of workers who quit their current job each month as a share of total employment. However, this trend also shows the disruptions in our economy go beyond the positions that are currently open directly.

One of the biggest questions facing economists today is, “Where did the workers go?”

One reasonable hypothesis is the possibility that many of the men and women who left the workforce are receiving unemployment insurance or other benefits from the government. However, the data do not support this theory. Indeed, the number of men and women who receive unemployment insurance in West Virginia now stands at just over 8,000. By contrast, the figure stood at over 14,000 just before the COVID-era in early 2020, and it peaked at over 140,000 during the worst of the COVID-19 recession. Similarly, the number of men and women receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families benefits in West Virginia has fallen and now stands substantially below its early 2020 level.

While this is not a fully resolved question, the clearest current explanation is simply that many men and women retired early as a result of the health concern and overall chaos that the pandemic and recession created. A recent analysis from the Roosevelt Institute shows that 90% of the men and women who left the labor force since late 2019 were over 55 years of age, suggesting a surge in early retirements. The presumption is that many of these men and women wanted to escape the economic and public health turmoil our economy was facing, and they simply opted to retire early, even though their retirement savings were not quite as high as they would have been during normal economic conditions.

Economists are monitoring what we term unretirements—that is, men and women who left the labor force for retirement but are now deciding to re-enter the workforce. The unretirement statistic has recovered to its early 2020 position, but further gains are needed to erase this broad problem. Right now, the economy is in a wait-and-see mode where we continue to look for labor force entries from a variety of sources as well as increased mechanization that may eliminate the need for some jobs altogether. However, it is hard to predict how long this evolution will take.

As if these worker shortages were not creating enough economic distress, we must also consider the implications of this problem. It is clear employers are having to pay more for workers since they now have to compete more aggressively for employees. Much of the costs of increased wages are then being passed on to the consumer in the form of higher prices. It’s not surprising then that workforce shortages, combined with supply chain constraints, have combined to drive inflation to its highest rate in 40 years.

Innovating a Way Out of Supply Chain Constraints

How do a few firms in the same industry get through a devastating global crisis comparatively better? The pandemic is in its second year, and a new, aggressive geopolitical event is shocking global supply networks still in recovery mode. With 94% of Fortune 1000 companies and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) alike experiencing disruptions, many see supply chains broken and lacking resilience. However, there is light at the end of the tunnel in the form of digital innovation and an entrepreneurial mindset.

Supply network design considers regional specialization, labor costs, market access, natural resources and economies of scale and often involves thousands of globally interconnected firms. However, their interconnected nature makes the system vulnerable to shocks or constraints in any of its parts, as we are currently experiencing.

Nevertheless, the current constraints provide valuable lessons. Digital innovation can assist organizations in understanding and strengthening supply networks and their operations and implementing some of the learnings.

The global crisis exposed the dependence on single suppliers in specific regions, raising the need to produce closer to home. While such is necessary at some level, it is insufficient. Organizations also need to diversify sources. For instance, a series of recent factory fires in the U.S. caused widespread supply disruption. Resilinc’s EventWatch monitoring sent out 1,946 factory fire alerts in 2021, increasing 129% year over year. Also, bringing certain value chain stages back is neither easy nor cheap.

Nonetheless, digital capabilities make it possible to operate in places not traditionally considered. In addition, the flexibility of digital supply networks and processes can make it easier and faster for an organization to change plans quickly.

Another aspect that became clear during the pandemic was the lack of visibility into the supply network system. Most companies see their tier one suppliers—their direct and immediate source. However, often they have no visibility into tiers deep into their networks. Over 70% of procurement professionals revealed to Reuters last year concerns about their supplier intelligence not being better to crisis-proof supply chains. Without knowing who is doing what and where further into the network, organizations have less time to mitigate potential disruptions. Digital capabilities can enable real-time visibility, dynamic planning and provenance.

The pandemic also highlighted supply chains and organizations’ dependence on brave frontline workers and the importance of preparing them to operate where and when needed. It also highlighted the difficulty of finding workers to fill current manufacturing and supply chain positions. Such constraints should persist in the coming years. Digitization makes it possible to shift people from dangerous or repetitive tasks to more challenging and rewarding functions. During 2020, industrial users, for instance, increased investments in robots by nearly 30%.

Almost every transportation mode has also faced and imposed constraints. For instance, Los Angeles and Long Beach ports, responsible for about 40% of the inflow of sea cargo into the country, faced lines of over 100 ships waiting to dock. Transatlantic air cargo capacity at the onset of the pandemic was down over 50% compared to the previous year. Organizations can leverage digital capabilities to gain visibility into available logistics capacity. They can make real-time transportation mode decisions based on costs, route and volume at more sophisticated levels, as Amazon is increasingly doing.

Of course, investing in supply chain and organizational digitization can help mitigate various risks while also creating new ones. As organizations build digital capabilities and employ a robotic-assisted workforce, Internet of Things and wearables, the security risks grow. All sectors face a surge in ransomware attacks. By some estimates, cybercrime will cost the world an alarming $10.5 trillion annually by 2025.

Experimenting with digital technology and building capabilities requires an innovation and entrepreneurial mindset. Larger companies can often more readily innovate and create digital capabilities. However, due to the interconnected nature of supply networks, it is to their benefit to also invest in developing their smaller suppliers’ technological capabilities.

Many organizations and initiatives in the Mountain State form a robust innovation ecosystem of resources that organizations can tap. They include many resources at WVU, including the John Chambers College of Business and Economics’ expertise in analytics and cybersecurity, Wehrle Global Supply Chain Lab, Morris L. Hayhurst LaunchLab, Dr. Thorsten Wuest’s lab and resources at the Benjamin M. Statler College of Engineering and Mineral Resources, as well as programs at Marshall University, the Robert C. Byrd Institute and others.

Global supply networks are increasingly vulnerable to disruption. Digital capabilities can help companies understand, diversify, reconfigure and make their supply chains and operations more resilient. Moreover, those with more mature digital capabilities are coping better with the global crisis. Digital innovation is not about technology or replacing human labor, however. Instead, it is about creating capabilities to augment human potential and enable superior value creation.