Growth in the Commercial Climate Weather Industry

By Cathy Bonnstetter

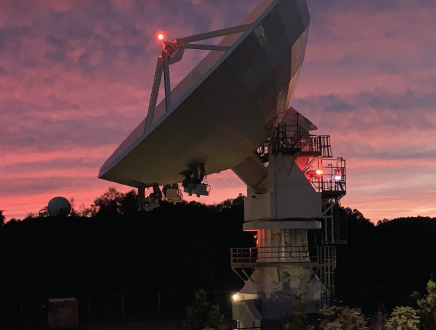

GOES-R Series Ground System Consolidated Backup I-79 Technology Park.

All hours of the day and night, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is gathering terabytes of information from multiple satellites at the West Virginia High Technology Foundation’s I-79 Technology Park. As the data silently streams through the satellites, Jim Estep, High Technology Foundation president and CEO, hears money and opportunity pouring into the Mountain State.

“I want to make every West Virginia coal miner a data miner,” Estep says. “A lot of the commercial climate weather industry is taking note of North Central West Virginia.”

In 2013, NOAA began operating its Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite Ground Center at the technology park. NOAA followed that satellite installation with its Joint Polar Satellite System ground station, which was completed in 2014. Last year, NOAA began operating the Space Weather Follow On Satellite ground station at the park. These satellites collect weather information for the Northern Hemisphere of the planet.

“No other place on the planet has three ground stations and a supercomputing center,” Estep says. “Most of the world’s climate and weather data comes through Fairmont, and that is massive.”

NOAA began operating its supercomputer at the I-79 Technology Park in 2011. General Dynamics, another park resident, services that contract. NOAA brought its cybersecurity to Fairmont in 2013 and expanded its cybersecurity to include the U.S. Department of Commerce in 2018. NOAA awarded that cybersecurity contract to technology park resident Leidos.

The atmospheric data gathered at the technology park has multiple commercial uses. Estep notes that cities use it to plan how much road salt to purchase, agricultural entities use it to plan their crops, and shipping companies use it to track the constantly changing shipping lanes. Airports also use the data, as well as water management entities.

“The Weather Channel is just the tip of the iceberg,” Estep says. “Most people don’t know that this collected data is the basis of a $7 billion commercial climate weather industry that NOAA believes will balloon to $14 billion.”

Estep says he believes Fairmont and North Central West Virginia can become the epicenter for a commercialized weather data boom. This data is free from NOAA; however, it is incredibly expensive to access.

“It is hard to work with that data. There are a lot of barriers, but it’s still $7 billion,” says Estep. “If you make working with the data easier, apply supercomputing and artificial intelligence, you can get new types of information that people are willing to pay for. That is what will double the market from $7 billioin to $14 billion.”

NOAA has worked with Amazon Web Services, Microsoft and Google to put some of this data on their cloud services for commercial use. However, the data is so massive that it just does not fit. This is where Estep’s plan, more than 15 years in the making, comes into play.

“You can’t imagine the amount of data,” Estep says. “They just can’t pump it all in there. What we proposed to each of those companies is coming here to Fairmont. Why not build their data centers here? These companies could run their own fiber into the building collecting the data and reduce their costs, while putting more data in their cloud environments.”

Estep is building a high technology center with federal agencies as anchors. Once an agency commits to Fairmont, other technology businesses can move to the park to service their contracts. The foundation’s business model includes a great incentive: free land for federal anchors. Transforming the Mountain State into a high-tech weather epicenter is a life-long professional goal for Estep, and he says it is a game changer in the making for West Virginia.

“I believe this is the biggest opportunity the state has ever seen,” Estep says. “We spent the last 15 years getting the hard part in place. We are having negotiations with the cloud service providers. We are working very impressively with the state to run the fiber. We need to get these cloud providers here, but that’s achievable. Having at least one of those cloud service providers in the park, it is substantially more likely we can capture a significant, if not majority, market share of the projected multibillion-dollar expansion of this industry.”

While the wheels are in motion, Estep still needs the state’s help to complete this transformation puzzle.

“The state needs to help us get at least one of these cloud service providers. I am working with them to try to do that,” he says. “The state needs to help us make sure we are establishing a pipeline of innovators and entrepreneurs. That is in motion, too. We need to reach out to the development office. We need a full-blown program to make every climate company aware of what we have so maybe they will relocate.”

Paramount in the project is a workforce ready to jump into big data as entrepreneurs or professional employees.

“In West Virginia we were training people to work in the mines, which was a great job, but it only required a high school diploma,” Estep says. “People look at our workforce and see education is really low because we created no jobs that required it.”

The West Virginia Higher Education Policy Commission has plans in place to prepare more of the state’s young people to work in the knowledge sector. With the West Virginia Board of Education among its partners, the commission’s science and research division has compiled Vision 2025, a five-year plan to accentuate STEM classes and jobs.

“Computer science and data is one of the four key research areas identified in Vision 2025,” says Julianna Serafin, Ph.D., director of the science and research division. “That is exactly the kind of background people will need to use this weather data they are accumulating at the high technology park.”

Serafin says the division wants about 30% of the people who enroll in STEM degree programs in West Virginia to complete the program within four years. In 10 years, they want to double that number to 60%.

Successful commercialization of weather data at the I-79 park will bring people to the Mountain State and stop the state’s brain drain with professional opportunities it can provide, according to Estep.

“We want the existing $7 billion industry to migrate here, but with this new use of cloud technology, it will double,” he says. “I am hoping this expansion from $7 billion to $14 billion will be indigenous. This is not pie in the sky; it’s here. If we can get at least one of the data centers here, we will see significant movement in five years. We are so close to what could be transformative. This will help diversify our economy and eclipse anything we hoped for. Coal is our past; data is our future.”